Download the article:

This article argues for the importance of quiet, introverted leaders in international schools as a counterbalance to the extroverts who seem to make up the bulk of leadership posts in these institutions. It builds on essays by Liz Jackson (2021) and Bruce Macfarlane (2021), which explore leadership in university settings. These authors examine the de facto expectations of leaders to be outgoing and forceful, but challenge the idea of the heroic leader, suggesting that more introverted people can make significant contributions to university leadership. Before joining my current university as a lecturer, I held several senior leadership posts in international schools. In my current role, I continue to work with school leaders, and so now have a ‘foot in both camps.’ I look here at leadership in international schools through the lens of my own experience in this setting.

Heroic leaders for schools in crisis?

As their mission statements make plain, international schools these days seem keen to produce ‘the leaders of tomorrow.’ Judging by what they are looking for in their senior leaders, they have a very clear idea of what such leadership entails. I recently looked at some job advertisements for school leadership positions, and found, within a few minutes, that schools all over the world are looking for ‘motivated and dynamic’ leaders who are ‘innovative and inspirational,’ ‘enactors of positive change’ and who have ‘a commitment to growth and excellence’ (to mention just a fraction of the superlatives I came across).

Macfarlane (2021) observes that descriptions of academic leadership roles at universities appear to require individuals with the qualities of superheroes to urgently address what might be imagined are weighty and urgent problems in universities. Schools, too, it would seem, are in an endless state of crisis and, judging by the job advertisements that schools are posting, modern versions of Henry V are needed to fill these positions – crusading, visionary, and confident in the extreme. In a word – heroic. I certainly do not fit the bill. More like Henry’s not-very-kingly son (also Henry), I like to be alone, to read books and to write, to learn new things, to go for walks. I do like to spend time with people, preferably one or two at a time, talking and listening to them. Most of all, I like to sit quietly and just think. So what was I doing for all those years? Was I really a ‘leader’? How was I contributing to nurturing those ‘leaders of tomorrow’?

Chance and duty

School leadership is an aspiration of many teachers. Indeed, there is often pressure on teachers to seek positions of leadership, and those who remain – and wish to remain – as classroom teachers well into their career are sometimes seen as being either less capable, not very ambitious (which is, it seems, a bad thing) or not wishing to contribute to the school. As such, not seeking promotion can be seen as a professional, and even a personal or moral, deficiency.

There seem to be two problems with this kind of culture. First, once on the leadership track, teachers tend to stay on it and not move back into the classroom. As such, school leadership mirrors what Macfarlane (2021) notes is the case in universities, where academic leadership is generally seen as a career choice and something separate from being an academic. Being out of the classroom is less a (time limited) duty, and more something to aspire to. A second problem lies, I suggest, in the way leaders are perceived – visionary, transformational, heroic. But not all of us are heroes, and heroes are not always needed. Indeed, they can be exactly the wrong kind of people for the job.

Like Liz Jackson (2021), I was very much an ‘accidental leader.’ I was, in a sense, thrown into something for which I was not prepared or trained, and did not have the temperament or even the desire. I came to see leadership as a positive thing in two ways. First, I felt it was an excellent learning opportunity. If being uncomfortable is a prerequisite for learning, then this was the opportunity par excellence. I did learn a lot. I became a politician. I grew a thick skin. I found my own voice. Second, I saw leadership as a kind of duty. Always a burden, I thought that here was a chance, however uncomfortable, to do something useful. These two positives culminated, eventually, in the confidence to enact my own values and do something I thought was genuinely worthwhile. I suppose I ‘leaned in’ to something which I did not feel came very naturally. I gained a lot, but one thing I never got was comfortable. I always felt I was swimming against the tide. If I was not up there on stage, putting on a show, being ‘visible,’ then I was not doing the job. I could never really be me and, at the same time, the kind of heroic leader which, I felt, the school wanted.

My own experience, however, instantiates what I believe to be the downside of an over-reliance on one kind of leader, and the potential of a different, more understated kind of leadership to counterbalance the dominant model of leader-as-hero which pervades the culture of international schools.

The downside of visionary leadership

In his article, Macfarlane (2021) questions the widely held contemporary view that extroverts make better leaders. Extroverts do have much to commend them of course – the energy, passion and enthusiasm they offer are all valuable qualities which can be turned to good organisational use. But in my experience, a surfeit of such extroverted leaders exists in international schools. This is hardly surprising and simply mirrors a long-time societal trend of valuing outgoing and vocal individuals over their quieter counterparts.

Although between a third and a half of all individuals are introverts, modern schools are set up for extroverts’ need for stimulation. But, as Susan Cain points out in her book Quiet (2013), solitude is a crucial ingredient to creativity. Darwin spent much of his time alone. Newton was a famous introvert who would lock himself inside his laboratory for weeks at a time. Montaigne was happiest alone with his books in his tower. In schools there is an excessive emphasis on the things that drain introverts – community, collaboration and communication. These are important, of course, but they now dominate classrooms. Even school libraries are often noisy places, full of students ‘collaborating.’ While the students collaborate, teachers work in ‘teams’ to plan lessons, and leaders occupy positions in groups which are, also, given the misnomer of ‘teams.’ But throwing people together – mostly extroverts – rarely results in creativity or good leadership, however, but simply in a cacophony of voices all trying to speak more loudly than everyone else. In a world of extroverted leaders, everyone has something to say, but nobody really listens. In my tenure on such ‘teams,’ I rarely felt heard. I rarely had a chance even to speak. I could sit in a two-hour meeting without saying a word – and often did.

Schools miss out on a huge store of potential by not actively encouraging such reluctant potential leaders to come forward, and by not building a culture where introversion, quietness and solitude are valued. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates explains that the only person who is qualified to be a ruler is someone who does not desire such a position. Plato’s philosopher kings are focused on self-cultivation and are not interested in politics and other day-to-day concerns which take them away from the study of goodness, beauty and justice. In other words, those most suited to leadership are reluctant to take it on (Lorkovic, 2019). The opposite of Plato’s ideal leader is the Machiavellian prince, a ruthless and ambitious person devoted to power for its own sake and mostly concerned with self-preservation and personal advancement. I am not suggesting that senior leaders are all Machiavellian (although I have come across more than a few), but principals and heads of school tend to be dominant and forceful in their approach – how else would they get to such an elevated position? Gardner-McTaggart (2018) describes international school principals as ‘culturally powerful individuals who transform schools to fall in line with their own societal values’ (p. 159). In the end, it is often the vision of one charismatic, dominant individual that is imposed on the school, whatever pretensions of staff input might exist.

This begs two questions. First, who or what does such charismatic leadership serve? International schools, like universities, are now marketplaces, driven to compete for ‘customers’ who can choose to take their money elsewhere. The danger, therefore, is that neoliberalism bends the vision of school leaders to something mundane and narrow, at best, and harmful to our children and their teachers at worst. Henry V was moved by some kind of higher purpose (bizarre as it might now seem to us). School leaders are often moved, at least in part, by a desire to improve their school’s grades and standing in the eyes of their ‘clientele,’ a sad, second rate, myopic vision indeed.

This leads to the second, rather central, question: what is the purpose of international schools? Indeed, what is the purpose of any educational institution? As they chase academic results, prestige and reputation increasingly fiercely, positioning their ‘clientele’ for success in the job market, one wonders: is this all they are for? William Corey, a nineteenth century Master of Eton College (founded, incidentally, by Henry V’s scholarly but strikingly unheroic son), thought that the purpose of a ‘great school’ was to acquire ‘the habit of attention, the art of expression, the art of entering quickly into another person’s thoughts, the habit of submitting to censure and refutation, taste, discrimination, mental courage, and mental soberness.’ I suggest that a more humane, expansive, and important agenda be served by a different kind of leader.

Quiet school leadership

My first degree was in Chemistry. The final year involved doing some original research. I ended up being part of a group, the head of which was an obviously very bright chemist who, as far as I could tell, made no attempt to build or lead a team. There were no ‘team-building’ activities, no vision and mission statements, no group planning, no inspirational or motivational speeches. He spent his time as an academic, and would walk around being friendly and encouraging, dispensing the odd bit of advice and trying to help out where he could. The group worked well, published interesting and useful research and enjoyed some great camaraderie. I found our ‘boss’ to be a kind and gentle and generous man who, without knowing, perhaps, was enacting Nodding’s (1988) ethic of care through a focus on relationships, being attentive to all the little interactions which occur between people every day, and simply being there for us without any obvious agenda except to be helpful to us. It seems to me that people like this are an ‘untapped resource,’ one which schools chronically undervalue as potential leaders. Because they do not fit into the heroic mould, they are overlooked and undervalued. But if we agree with William Corey that (among other things) school is about developing attitudes and character and, more broadly, an ability to live well in the world, then I suggest that quiet leaders have an important role.

As far as I can tell, most people do not become teachers because they care passionately about some organisational vision or a set of KPIs. They are motivated, to a large extent, by the desire to make a difference in young people’s lives. It makes sense, then, that relationships are what matter most. I want to suggest that, along with the Henry V’s of the world, necessary as they are in certain contexts and for certain purposes, we also need educational leaders – both in tertiary institutions and international schools – who focus on relationality, enacting an ethic of care, embodying the essence of living well.

Unsurprisingly, research shows that the quality of relationships has a significant impact on teachers’ wellbeing (Lopes & Oliveira, 2020). More distributed leadership practices have been associated with higher levels of job-satisfaction and self-efficacy among teachers (Aldridge & Fraser, 2016; García Torres, 2018; Sun & Xia, 2018), and a collaborative climate benefits their mental health (Liu, Bellibaş, & Gümüş, 2020).

Relationships flourish when there is humility – a reluctance to assert authority, a reticence to make bold changes, and an absence of hubris. Verse 60 of the Tao Te Ching advises leaders that ‘ruling a great country is like cooking a small fish. Too much turning will spoil it.’ Jackson (2021) writes that vulnerability, a willingness to be wrong and to open to questioning and the possibility of being mistaken, is essential to education, at any level, and this strikes me as also being an essential leadership quality. She sees the ‘vulnerable leader’ as courageous, but in the sense of recognising the limits of one’s vision. Courage is often (mis)construed as something almost warrior-like, but I am struck by Jackson’s (2020) way of seeing courage as a kind of openness or authenticity. To me, this is the heart of the matter. Recent research confirms that authentic leadership (over transformational leadership) is associated with the psychological empowerment of teachers (Zhang, Bowers, & Mao, 2020), a finding which resonates with my own experience.

Macfarlane (2021) also sees a mentality of duty as central to being an academic, and school leadership should, perhaps, also be seen more as a (time limited) burden than a reward or the culmination of a successful career. Personally, I was glad to let go of the burden. Senior leadership in international schools helped me to grow and to learn a great deal, and also allowed me to make what I believe was a helpful contribution to the systems which supported the young people and families we served. But I never became comfortable, never lost the sense that I was swimming upstream by not being more extroverted. In the end, I felt that by being myself, by being quiet, I become marginalised. I could have influence, but only at the cost of being genuine, being me, acting a certain kind of role. And so, after years of having carried this burden, I left my senior leadership post – and breathed a huge sigh of relief. In an important sense, this was energising for both me and the school – I could go on to do something new, and someone with new ideas could contribute to the school. But I was also sad that there was so little space for the kind of leadership that I felt most at home with.

Conclusion

If my students were supposed to be the leaders of the future, becoming ‘motivated, dynamic, innovative and inspirational enactors of positive change,’ then I may have failed to be a good role model. But on my last ever day as a senior school leader, a student made a point of coming to see me. He told me that sitting quietly in my room and talking to me over a period of several months had made a big difference to him. I don’t imagine that my student saw much of an inspirational change-maker in those meetings, but in that quiet, reflective space, something useful and perhaps important happened.

I try to stay open to new possibilities, but now when people ask me what I like most about my job, I say, ‘I’m not a leader.’ I don’t have to (pretend to) be a hero. Perhaps school boards might bear in mind the ancient wisdom of Lao Tsz as they recruit principals and heads of school. Chapter 17 of the Tao Te Ching is a vision of ideal Taoist leadership: ‘A leader is best when people barely know he exists. When his work is done, his aim is fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.’

References

Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2016). Teachers’ views of their school climate and its relationship with teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 291–307.

Cain, S. (2013). Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. Broadway Books. Penguin.

García Torres, D. (2018). Distributed leadership and teacher job satisfaction in Singapore. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(1), 127–142.

Gardner-McTaggart, A. (2018). International schools: leadership reviewed. Journal of Research in International Education, 17(2), 148-163.

Jackson, L. (2021). Humility and vulnerability, or leaning in? Personal reflections on leadership and difference in global universities. Universities & Intellectuals, 1 (1), 24-29.

Liu, Y., Bellibaş, M. Ş., & Gümüş, S. (2020). The Effect of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Teacher Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Supportive School Culture and Teacher Collaboration. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 1–24.

Lorkovic, E. (2019). On willing and unwilling leaders. Crisis Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.crisismagazine.com/2019/on-willing-and-unwilling-leaders.

Macfarlane, B. (2021) In Praise of Quiet Leadership. Universities & Intellectuals, 1 (1), 36-42.

Noddings, N. (1988). An ethic of caring and its implications for instructional arrangements. American journal of education, 96(2), 215-230.

Sun, A., & Xia, J. (2018). Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. International Journal of Educational Research, 92(April), 86–97.

Zhang, S., Bowers, A. J., & Mao, Y. (2020). Authentic leadership and teachers’ voice behaviour: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of interpersonal trust. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 1741143220915925.

To Cite This Article:

Harrison, M.G. (2021). Quiet leadership in schools: A personal reflection. Academic Praxis, 1: 5-17.

Other Recent Articles

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more Ukrainian Academics in the Times of War On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a brutal full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. Eight years after the invasion of the Crimea and Donbas, the Russian government acted on Vladimir Putin’s assertions that Ukraine is not (and should not be) a country – a view deeply ingrained in propaganda-addled Russian popular opinion, to attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state and identity. The Russian army has been bombing Ukrainian cities, including residential areas, universities and schools.… Read more

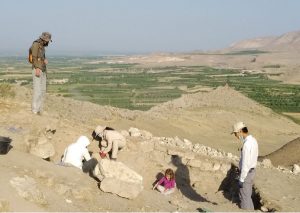

Ukrainian Academics in the Times of War On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a brutal full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. Eight years after the invasion of the Crimea and Donbas, the Russian government acted on Vladimir Putin’s assertions that Ukraine is not (and should not be) a country – a view deeply ingrained in propaganda-addled Russian popular opinion, to attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state and identity. The Russian army has been bombing Ukrainian cities, including residential areas, universities and schools.… Read more Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more

Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more

Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more Experiential Learning at the University of Hong Kong Innovation in education always starts with an idea which gradually develops into on-the-ground practices, and can then spread to different areas in an education institute. In higher education, innovation can be demonstrated in various ways. While people might relate innovation naturally with the use of new and advanced technology, curriculum can also be an area where innovative ideas are applied. In fact, as scholars have highlighted, innovation aimed at transforming the curriculum was beneficial not… Read more

Experiential Learning at the University of Hong Kong Innovation in education always starts with an idea which gradually develops into on-the-ground practices, and can then spread to different areas in an education institute. In higher education, innovation can be demonstrated in various ways. While people might relate innovation naturally with the use of new and advanced technology, curriculum can also be an area where innovative ideas are applied. In fact, as scholars have highlighted, innovation aimed at transforming the curriculum was beneficial not… Read more Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more

Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more

Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more

Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more