Download the article:

Academic-Praxis.2.19-26.Oleksiyenko.pdf

Academic-Praxis.2.19-26.Oleksiyenko.pdf

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a brutal full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. Eight years after the invasion of the Crimea and Donbas, the Russian government acted on Vladimir Putin’s assertions that Ukraine is not (and should not be) a country – a view deeply ingrained in propaganda-addled Russian popular opinion, to attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state and identity. The Russian army has been bombing Ukrainian cities, including residential areas, universities and schools. Russian soldiers have been killing, raping, and torturing thousands of civilians, including children, their mothers and grandparents. More than four million Ukrainian citizens, mostly women, children and the elderly, fled to Poland, Romania, Hungary, and other countries in the EU and beyond. Forty million people, including female and male members of the armed forces, medical workers, teachers and nurses, stayed back in the hope that they would be able to survive, resist and defeat the Russian aggressor.

Ukrainian professors and students have been integral participants in the unfolding tragedy and heroic fight for survival. Some joined the territorial defense or regular army battalions to defend their country. Others launched various humanitarian projects, fundraising campaigns, and refugee support groups. Those who could, continued to teach. Many also joined the info-war, defusing misinformation and propaganda, and informing their colleagues in Russia and other countries about #PutinWarCrimes (a hashtag trending on social media for weeks).

As the Russian blitzkrieg failed, and turned into lengthy and debilitating combat resulting in staggering devastation and death, Ukrainian scholars and university administrators have been pressed to think strategically about their future engagements with Russia and the world. For many, Ukrainian-Russian relations have no future, and they do not want to participate in anything that triggers memories of Russia. Their choice is driven by ongoing civilian massacres and intentional destruction of Ukraine’s cultural heritage. Ukrainian hospitals, schools, universities and museums are being razed to rubble. A theatre sheltering civilians in Mariupol was bombed killing many of those inside. In the invaded regions, buses and cars transporting civilian refugees have been mowed down. Hit squads roamed around hunting down and shooting civic leaders, teachers, teacher trainers, and professors. Horror stories are piling up from cities such as Mariupol and Bucha. A medical doctor in Zaporizhia, for instance, reported that girls released from occupied Mariupol, the oldest of whom was ten years old, had recto-vaginal tears. Reports of mass graves in Bucha triggered global outrage, inflamed even more when the Russian government began to twist the truth and shift blame onto the West and NATO, in addition to ordering the use of mobile crematoria to hide their war crimes in places that have yet to be liberated. Who would want to offer any words of appeasement amidst these atrocities? What kind of a university professor?

Disbelief grew as the Russian Union of Rectors, representing 700 rectors and university presidents, proclaimed full and patriotic support for the fascist regime in their country (Lem, 2022). Many Russian analysts used their academic authority to shore up Putin’s pseudo-historical and neo-fascist arguments denying Ukraine’s right to exist, and justifying the use of force to “de-Nazify” people like President Zelenskyy, who cherishes his Jewish heritage and whose grandfather fought in the Red Army during World War II. In Kharkiv, a 96-year-old Holocaust survivor, Borys Romanchenko, was killed by the Russian shelling. In Kyiv, five people were killed when a Russian missile struck the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial, the site of one of the largest World War II mass graves in Europe. Russian soldiers burned books on Ukrainian history and culture, destroyed monuments of Ukraine’s historical figures, and eliminated documented evidence of the Soviet genocide of Ukrainian people. Among the losses was the Ukrainian Security Service archive in Chernihiv, which housed more than 12,000 folders about the KGB and the repression of the Ukrainian population by the Soviet regime, including during the Holodomor. In despair, some Ukrainian scholars still believed that it might make sense to engage Russian academic opposition into international dialogues and help them amplify messages on the Russian fascist regime and its war crimes. Other Ukrainian scholars, however, raised concerns about security in international S&T projects, given heightened FSB control over Russian scientists and students since the start of the war. In addition to calling for the termination of joint projects with Russians, academic activists took part in letter writing to international scientific associations, asking them to revoke Russian membership, as well as conference participation and facilitation.

Some prominent Western universities terminated or suspended their collaborative agreements and programs with Russia. “The European University Association – the continent’s largest university lobby – announced it had suspended 12 [Russian] member institutions whose heads had signed the letter, which it said was “diametrically opposed to the European values that they committed to when joining EUA” (Lem, 2022). Meanwhile, a range of universities opened new places, services and scholarships to support Ukrainian scholars and students at risk. Erudera.com, “the world’s first education search platform backed by AI” listed over 70 universities in 20 countries providing such support. Numerous scholars in the West circulated information about research positions and scholarships in their sponsored projects, welcoming their Ukrainian peers and offering resources to help displaced scholars settle in at their universities. These engagements reflected the growing solidarity of the global liberal order, and were indicative of a moral stance taken by both politicians and academics. Despite their competing worldviews and all-to-frequent reliance on intellectually lazy “whataboutism”, the academic community in democratic countries has been remarkably united in taking a zero-tolerance stance toward Russian war crimes. In an effort to counter Russian propaganda, Ukrainian scholars organized numerous seminars and webinars to answer questions regarding Ukraine’s politics, history, and culture. New publications and podcasts in a variety of languages sprang up. Ukrainian scholars also launched special issues in journals, and began to consider approaches to de-russifying the Ukrainian identity and narratives.

These endeavors revealed the enormity of the challenge of deconstructing Russian propaganda and myths about Ukraine, and the dominance of Russo-centric analysis propelled by Western scholars influenced by Soviet studies and captivated by Russia. The expansion of the “Russian world” after the Soviet demise (i.e., the Russo-centric narratives controlled and promoted by Russian embassies and their agents abroad, and funded by Russian petrodollars) left a significant imprint on the Western psyche. As the prominent historian and public intellectual Anne Applebaum (2022, March 29) noted (with subsequent support from such influential public figures as former US Ambassador to Russia, Professor Michael McFaul of Stanford University), “these Russian attitudes are often reflected in Europe and the US, where anyone who studied Russian also imbibed the Moscow view of history. Most of the great Western historians writing about Russia (for example Kotkin) were never interested in Ukraine”. Instead, a fascination with Russian ballet, literature (focusing on several mainstream writers like Dostoyvesky), and Russians’ penchant for champagne and caviar, kept the cerebral West excited, intrigued and drawn into the orbits of the “world” created by Russian soft power managers. The Sputnik syndrome and memories of the Cold War, governed by the doctrine of mutual assured destruction, kept the Euro-Atlantic imagination focused on appeasing, instead of dethroning the Russian tyrant.

Global solidarity in defense of democracy was often overlooked in the past (Applebaum, 2022). In the present, as Mounk (2022, March 31) remarks, the international solidarity is not consistently assured. After a debate on German TV, the Johns Hopkins University professor noted: “there is a complacent faith that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has finally shocked Europeans out of their long-standing habit of appeasing dictators and prioritizing their economic self-interest. I have long worried that this is naive. Tonight, my concern increased tenfold.” Many illiberal governments also hesitated to support Ukraine and as the voting results in the United Nations Human Rights Council showed – a significant number of authoritarian regimes, primarily in developing countries, were more supportive of Russia than Ukraine.

Nonetheless, the David-Goliath battle waged by the heroic Ukrainians has certainly shaken the Western world’s easy complicity, as well as the myths of Russian superiority. The Ukrainians’ fight, often without proper weapons, but with courage and firm loyalty to the ideas of freedom and democracy, time and again demonstrates that imperial constructs cannot have a future. Among the lessons we are learning now is that the solidarity of Western intellectuals, professors, artists, athletes and other public figures can have an exceptional impact globally. Together with Ukrainian partners, they were able to create pressure on their governments to provide military and financial support in the most critical moments of the Russian invasion, and thus facilitated opportunities for the Ukrainian civil society to defend itself. Yale Professor Timothy Snyder has argued that “Ukrainian history is exceptional only insofar as it embodies major trends with unusual intensity.” It seems that the trends it is inspiring now will lead to long-term resilience and global solidarity for democracy.

References

Applebaum, A. (2022, March 31). There is no liberal world order: Unless democracies defend themselves, the forces of autocracy will destroy them. The Atlantic, Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/05/autocracy-could-destroy-democracy-russia-ukraine/629363/

Applebaum, A. (2022, March 29). Twitter Account: @anneapplebaum

Friedman, T. (2022, April 3). Putin Had No Clue How Many of Us Would Be Watching. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/03/opinion/ukraine-russia-wired.html

Lem, P. (2022, March 7). Russian rectors’ union echoes Kremlin propaganda on Ukraine. Times Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/russian-rectors-union-echoes-kremlin-propaganda-ukraine

Mounk, Y. (2022, March 31). Twitter Account: @Yascha_Mounk.

To Cite This Article:

Oleksiyenko, A. (2022). Ukrainian Academics in the Times of War. Academic Praxis, 2: 19-26.

Other Recent Articles

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more

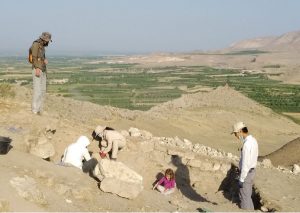

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more

Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more

Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more Experiential Learning at the University of Hong Kong Innovation in education always starts with an idea which gradually develops into on-the-ground practices, and can then spread to different areas in an education institute. In higher education, innovation can be demonstrated in various ways. While people might relate innovation naturally with the use of new and advanced technology, curriculum can also be an area where innovative ideas are applied. In fact, as scholars have highlighted, innovation aimed at transforming the curriculum was beneficial not… Read more

Experiential Learning at the University of Hong Kong Innovation in education always starts with an idea which gradually develops into on-the-ground practices, and can then spread to different areas in an education institute. In higher education, innovation can be demonstrated in various ways. While people might relate innovation naturally with the use of new and advanced technology, curriculum can also be an area where innovative ideas are applied. In fact, as scholars have highlighted, innovation aimed at transforming the curriculum was beneficial not… Read more Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more

Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more

Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more Quiet Leadership in Schools: A Personal Reflection This article argues for the importance of quiet, introverted leaders in international schools as a counterbalance to the extroverts who seem to make up the bulk of leadership posts in these institutions. It builds on essays by Liz Jackson (2021) and Bruce Macfarlane (2021), which explore leadership in university settings. These authors examine the de facto expectations of leaders to be outgoing and forceful, but challenge the idea of the heroic leader, suggesting that more… Read more

Quiet Leadership in Schools: A Personal Reflection This article argues for the importance of quiet, introverted leaders in international schools as a counterbalance to the extroverts who seem to make up the bulk of leadership posts in these institutions. It builds on essays by Liz Jackson (2021) and Bruce Macfarlane (2021), which explore leadership in university settings. These authors examine the de facto expectations of leaders to be outgoing and forceful, but challenge the idea of the heroic leader, suggesting that more… Read more Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more

Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more