Download the article:

Academic-Praxis.1.52-66.Cheung.pdf

Academic-Praxis.1.52-66.Cheung.pdf

Innovation in education always starts with an idea which gradually develops into on-the-ground practices, and can then spread to different areas in an education institute. In higher education, innovation can be demonstrated in various ways. While people might relate innovation naturally with the use of new and advanced technology, curriculum can also be an area where innovative ideas are applied. In fact, as scholars have highlighted, innovation aimed at transforming the curriculum was beneficial not only to the higher education institute by increasing its flexibility, but also to both the students and academics as teaching practices were improved (Hasanefendic et al., 2017; White & Glickman, 2007). In this essay, personal experience with an innovation practice of promoting experiential learning as part of the curriculum at the University of Hong Kong (hereafter referred to as HKU) will be shared in order to shed light on the significance of this kind of innovation to higher education in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the essay proposes some preliminary ideas on what more can be done to further disseminate this innovation strategy.

Innovation of Curriculum in HKU: Experiential Learning

The innovation strategy to be discussed in the following sections is the incorporation of experiential learning in the undergraduate curriculum at HKU. While the roots of experiential learning can be traced back to John Dewey, and later David Kolb in the 20th century, it had not been emphasized as part of the curriculum for HKU undergraduate programmes until the establishment of the Gallant Ho Experiential Learning Centre in 2012. With its establishment, resources could be better organized in order to provide support to various faculties across the university – from short-term assistance to staff developing experiential learning opportunities, to medium-term efforts to merge experiential learning into parts of various courses, and long-term in pushing for a paradigm shift in making experiential learning a “predominant mode of learning” (Gallant Ho Experiential Learning Centre, 2021).

As a student in the programme of Bachelor of Education and Bachelor of Social Sciences (double degree), I am in a position to elaborate more on how experiential learning is introduced as part of the curricula in both the Faculty of Education and the Faculty of Social Sciences at HKU.

Since 2015, experiential learning has become an important component in the curriculum in the Faculty of Education to help nourish future professional teachers. In the beginning, experiential learning was introduced as a co-curricular learning element in the form of non-credit bearing courses or programmes, both locally and overseas, but as the university was valuing it more over the years, and the number of students enrolled into these programmes was increasing, the experiential learning team began to organize credit-bearing courses and include experiential learning as part of other courses. Starting from the previous academic year, experiential learning even became a compulsory component for most of the programmes within the Faculty (HKU Faculty of Education, 2021). In organizing these experiential learning opportunities, the Faculty has been collaborating closely with numerous local and overseas institutes or non-governmental organizations, such as Ocean Park and Eastern Vision, which helped organize overseas programmes in Tibet. Given the wide range of learning opportunities, the Faculty also welcomed students from other undergraduate programmes outside the Faculty of Education to participate, in order to promote inter-disciplinary knowledge exchange among students. On top of these initiatives, undergraduate students in the Faculty of Education are required to finish teaching practicums in local schools throughout their studies, which offer them career-based professional training based on the notion of “learning by doing”. All in all, experiential learning is now an inseparable piece of the curriculum for different programmes organized by the Faculty of Education.

As for the Faculty of Social Sciences, experiential learning was employed in its curriculum as early as 2008. Since then, the two key themes of Social Innovation and Global Citizenship have become the cornerstones for promoting experiential learning within the Faculty.

These two themes were later made into credit-bearing courses that all undergraduate students of the Faculty of Social Sciences must take in order to finish their studies. On one hand, the Social Innovation course provides non-paid internship opportunities for students to experience real-life work with local community partners. On the other hand, Global Citizenship allows students to go overseas to participate in exchange programmes, internships or summer schools. The organization of the two experiential learning courses is demonstrates the “co-construction model of experiential learning” advocated by the Faculty of Social Sciences, which sees students as partners, teachers at the Faculty as facilitators, and community partners as co-educators (HKU Faculty of Social Sciences, 2021). In short, the Faculty of Social Sciences sees experiential learning as an important component of its curriculum, as it helps prepare students to develop high local and global awareness, which is essential for them to be impactful and productive members of a globalized society.

Personal Experience and Observations

My experience in experiential learning began in my second year of undergraduate study, when I took the Social Innovation course and was offered a chance to work as an intern in the office of one of the Legislative Councilors. In summer, I enrolled in the Global Citizenship course, travelling to Canada to work as an intern/researcher in the Canada-Hong Kong Library at the University of Toronto. After that, starting from year three, I had the chance to be a student-teacher, as I did my three teaching practicums across three years in three different secondary schools. In my final year of study, I also took two credit-bearing experiential learning courses offered by the Faculty of Education, which, at that time, were not yet made compulsory for Education major students. As I reflect on these experiences of experiential learning, there are two key takeaways:

1. Expanding Learning into Venues Outside of the Classroom

By taking different experiential learning courses, I was given opportunities to learn in some unexpected places: from a secondary school to a theme park, from an office in Hong Kong to a library in Toronto. In these courses, I had also taken different roles, such as researcher, teacher, mentor and office assistant. These opportunities allowed me to have first-hand experience of learning outside of a traditional classroom, and acquiring mere theoretical knowledge in readings. Let me share more specifically on two of the experiential learning experiences.

One of the experiential learning courses that I took in year five was to do a pop-up narration in Ocean Park Hong Kong. I had to work in a team to design activities for a pop-up narration about penguins in one of the exhibition halls in the theme park. Not only were we given the chance to learn about the lives of penguins and the ways to protect their habitats, but also to be creative and sensitive to the needs of the audiences, as we came up with ideas to convey certain messages to them via the pop-up booth. Ultimately, through numerous rounds of trials, we were able to identify the needs of audiences from different age groups, ethnicities and social backgrounds, and present our narration in ways that were interactive and effective in conveying our messages of conserving the environment for the sake of penguins. This was a great lesson in being an effective messenger and learning to narrate difficult and complex ideas in an interesting and engaging way to learners with different needs and prior knowledge, which is an important attribute to have for professional teachers.

Another experience was an overseas one, where I spent two months in Toronto, working as an intern/researcher in a university library. Within that period of time, I had the chance to get in touch with the Hong Kong diaspora community in Toronto, learning about their life stories, as well as conducting my own research project targeting them. This was the first opportunity for me to test the research skills and knowledge that I had learnt in class in a real-life context. By accomplishing a research project from start to finish all by myself, I was able to learn about qualitative research by actually doing it. Together with the advice given by my supervisors, and the follow-up teaching sessions after I returned to Hong Kong, the whole learning experience was fruitful and helped equip me for future studies.

2. Different Facets of Learning through Experiential Learning

The second takeaway from my experiential learning experiences is how learning can expand into different facets of life. As I took on different roles and learnt in different contexts, I was able to see that education extends beyond the passing on of knowledge through traditional in-classroom teaching and learning.

In order to become a professional and competent teacher, accumulating interpersonal skills is of great importance, as teachers need to collaborate with different actors in schools when teaching and learning, as well as conducting other daily administrative work. From working with others in internships and teaching practicums, I learnt to interact with people from different backgrounds, and pick up skills and norms when working with people from different levels of a hierarchy in a school or a company.

Furthermore, networking and social commitment are indispensable for one to thrive as a productive member of society. The internship experience in a Legislative Councilor’s office offered me great exposure, enabling me to establish networks with different stakeholders when organizing community events, and imparting me with the necessary skills to maintain a cooperative relationship with them. Also, the experiential learning of mentoring secondary school students coming from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds encouraged me to contribute to the people in need in our society and stay committed to them. All of these experiences enriched my undergraduate studies and led me to areas of teaching and learning beyond mere transmission of knowledge.

In a nutshell, the innovative elements of incorporating experiential learning into undergraduate curricula at HKU can be explained in two dimensions. From the perspective of learning, it is innovative, as it revitalizes the traditional way of learning observed in a Chinese cultural context. Having received elementary and secondary education in local schools, the learning that I had experienced was mostly carried out in unilateral transmission of knowledge via lectures. This traditional approach to education was signified by rote learning and striving for high marks or grades in public exams, which was regarded as the ultimate goal of basic education. By engaging in experiential learning, I was able to experience education in brand new ways that are interactive and practical. More importantly, most of the experiential learning courses were assessed on a pass/fail basis and hence, I no longer needed to see learning as a means to getting high grades, but was taught that learning could also be an end goal by itself. Thus, the innovative nature of experiential learning is particularly amplified in a context dominated by traditional Chinese ways of teaching and learning.

From a personal perspective, experiential learning transformed my perceptions of learning and continued to influence my attitudes, as I entered the job market. After graduation, as I took on the role of teacher in a local school and overseas institute, I tried hard to put the philosophy of “learning by doing” into practice with my students. Instead of only one- way teaching, I sought out more opportunities for them to experience learning by themselves, and at the same time, guided them to self-reflect on their own learning experiences. Therefore, the innovation strategy of merging experiential learning into the undergraduate curricula was able to renew my thinking, and continues to make an impact on my work upon graduation.

From my observations, there are certain elements contributing to the success of innovation in curriculum design at HKU, and also some areas for further improvement.

Keys to Success

Firstly, the university has developed different resources that can support the implementation of experiential learning as part of its curricula. The most obvious example of these resources is financial support. For a lot of undergraduate students, lack of money is a huge barrier preventing them from participating in experiential learning, especially the overseas opportunities. In view of this, the faculties were providing subsidies and scholarships to help students meet their financial needs. For my internship in Toronto, the Faculty of Social Sciences offered me a much-needed financial subsidy that helped make the trip and the subsequent learning opportunity possible. These resources are important supporting frames that hold up the architecture of experiential learning as part of the undergraduate curricula.

Secondly, HKU has established a strong network with community partners, both locally and overseas. From secondary schools to a theme park, from private companies to overseas higher education institutes, the success of all my experiential learning opportunities was dependent on these partners’ willingness to participate and commit. HKU was capable of making use of its established network with different partners in the community, and maintaining cooperative relationships with them, which laid the foundation for successfully implementing various experiential learning opportunities for its students.

Lastly, there are professional teams across different faculties that are responsible for developing and promoting experiential learning. From the previously mentioned Gallant Ho Experiential Learning Centre, which coordinates efforts at promoting experiential learning on a whole-school level, to the different experiential teams in various faculties that organize experiential learning courses and programs, the committed teams make it possible for the overarching vision of promoting experiential learning to be realized and developed in a professional and systematic way.

Opportunities for Improvement

Despite what HKU is able to achieve in innovating its curricula by promoting experiential learning, there are two areas that might need further improvement in order to magnify the benefits of experiential learning to more students.

First of all, the university needs to put more effort into encouraging students to get involved in experiential learning. The most direct way to achieve this is to make experiential learning a compulsory element of the curricula that all students are required to fulfill. While this was what the Faculty of Social Sciences had done through Social Innovation and Global Citizenship during my undergraduate years, experiential learning outside of teaching practicums were not popular among students from the Faculty of Education. Although the Faculty had recently made it a requirement for its students, more policies are still called for in order to motivate more students from different faculties to embrace experiential learning as an inseparable part of their studies.

Moreover, HKU needs to make more adjustments to the curriculum design, so that students can allocate more of their time of study to experiential learning. In my experience, I could only utilize my electives quota to enroll in extra experiential learning courses, that is ones that were not compulsory. If the university refines the undergraduate curricula to reallocate some of the course requirement from traditional courses comprising lectures, tutorials and coursework to experiential learning courses, students can enjoy more freedom and have more incentives to take those courses and enrich their learning experiences.

Experiential Learning in Higher Education in Hong Kong Going Forward

The story of HKU in innovating its curriculum with the introduction of experiential learning illustrates the value of experiential learning in renewing a traditional curriculum in higher education. In fact, a lot of previous studies already highlighted the benefits of experiential learning in cultivating various attributes in university students, including but not limited to creativity, problem-solving, students’ engagement and social innovation (Ayob et al., 2011; Cheung et al., 2019; Pappas et al., 2018). As early as the 2000s, local scholars had conducted studies on the impact of service learning, one form of experiential learning, on university students.

By engaging in service-learning opportunities, as argued in these studies, students were able to develop respect for diversity and social commitment, and gain motivation for personal development by conducting self-reflections on their learning process (Ngai, 2006; Ngai & Ngai, 2005). These studies proved and reiterated how beneficial it is to promote experiential learning in the higher education sector.

Apart from HKU, experiential learning has been garnering interest from different universities in Hong Kong. For example, Lingnan University developed a set of service-learning courses that emphasize students’ whole-person development and their commitment to community (Ma & Chan, 2013). The example of the Polytechnic University reaching out to a local center for the elderly to collaborate on organizing experiential learning opportunities for its students demonstrates the availability of resources and connections in local communities that universities can make good use of in creating experiential learning programmes (Fung & Fong, 2020). From the perspective of the institutes themselves, more resources are needed to enhance the implementation of experiential learning, including financial subsidies. Universities should also set aside specific departments to coordinate with both internal and external actors in organizing experiential learning opportunities. From the perspective of the higher education sector as a whole, there can be more cooperative efforts in promoting experiential learning across different institutes. These can range from academic conferences allowing for the sharing of experiences in organizing experiential learning, to establishing a common platform that makes use of the existing networks of universities and helps connect institutes with various community partners, to even co-organizing specific experiential learning courses or programmes. As more efforts are intentionally invested in innovating the higher education curriculum by promoting experiential learning, more students can enjoy the benefits brought by this unconventional way of teaching and learning.

Conclusion

The example of HKU incorporating experiential learning into its curriculum suggests that innovation needs to be relevant to different contexts. While “learning by doing” may be a common component for a lot of education systems across the world, especially those in the Western world, it can still be an innovative strategy given the usual practices and stereotype of teaching and learning observed in the context of Hong Kong. Thus, being sensitive to the contexts and needs of specific locations is always the key to designing and implementing a successful innovation strategy in higher education. As the higher education sector in Hong Kong continues to promote experiential learning in different curricula, more transformative ideas on curriculum development are still necessary. Hopefully, through trials and adjustments, these ideas can further innovate and revitalize the curriculum in higher education and lead higher education development in Hong Kong to new heights.

References

Ayob, A., Hussain, A., Mustafa, M. M., Shaarani, M. F. A. S. (2011). Nurturing Creativity and Innovative Thinking through Experiential Learning. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 18, 247-254.

Cheung, S., Pang, A., Lui, A. & Sin, K. (2019). Zai Rong He Jiao Yu Zhong Shi Jian Fu Wu Xue Xi Gai Nian: Ge An Shi Fan [Implementing Service Learning in the Context of Inclusive Education: A Case Demonstration]. Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal, 18, 1-13.

Fung, R. & Fong, B. (2020). Treasure in Elderly Care Learning: A Service- learning Experience at a Neighborhood Centre in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 15(2), 5-10.

Gallant Ho Experiential Learning Centre (2021). What is Experiential Learning?. Retrieved from https://ghelc.hku.hk/what-is-experiential- learning/

Hasanefendic, S., Birkholz, J. M., Horta, H., Sijde, P. (2017). Individuals in action: bringing about innovation in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), 101-119.

HKU Faculty of Education (2021). Message from the Experiential Learning Team. Retrieved from https://el.edu.hku.hk/introduction/message-from- the-el-team/

HKU Faculty of Social Sciences (2021). What is Experiential Learning?. Retrieved from https://www.socsc.hku.hk/sigc/what-is-experiential- learning/

Ma, C. & Chan, A. (2013). A Hong Kong University First: Establishing service-learning as an academic credit-bearing subject. Gateways (Sydney, N.S.W.), 6(1), 178-198.

Ngai, S. S. (2006). Service-learning, personal development, and social commitment: A case study of university students in Hong Kong. Adolescence, 41(161), 165-176.

Ngai, S. S. & Ngai N. (2005). Differential Effects of Service Experience and Classroom Reflection on Service-Learning Outcomes: a study of university students in Hong Kong. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 12(3), 231-250.

Pappas, I. O., Mora, S., Jaccheri, L., Mikalef, P. (2018). Empowering Social Innovators through Collaborative and Experiential Learning. 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 1080-1088.

White, S. C. & Glickman, T. S. (2007). Innovation in higher education: Implications for the future. New Directions for Higher Education, 2007(137), 97-105.

To Cite This Article:

Cheung, L. H. A. (2021). Experiential Learning in the University of Hong Kong. Academic Praxis, 1: 52-66.

Other Recent Articles

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more

Chinese Students Collaborating Across Cultures Does International Higher Education Benefit from Collaborations? International education is argued to create better opportunities for higher learning if university program designers engage both personal and collective agency in studies of foreign languages and societies (Oleksiyenko and Shchepetylnykova, 2021), and thus increase students’ chances for greater engagement with alternative learning styles and contexts (Li, 2014; Phuong-Mai, et al., 2005). Yet, achieving a highly efficient design for cross-cultural learning is a challenge when courses prioritise technical… Read more Ukrainian Academics in the Times of War On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a brutal full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. Eight years after the invasion of the Crimea and Donbas, the Russian government acted on Vladimir Putin’s assertions that Ukraine is not (and should not be) a country – a view deeply ingrained in propaganda-addled Russian popular opinion, to attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state and identity. The Russian army has been bombing Ukrainian cities, including residential areas, universities and schools.… Read more

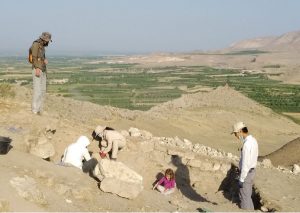

Ukrainian Academics in the Times of War On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a brutal full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine. Eight years after the invasion of the Crimea and Donbas, the Russian government acted on Vladimir Putin’s assertions that Ukraine is not (and should not be) a country – a view deeply ingrained in propaganda-addled Russian popular opinion, to attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state and identity. The Russian army has been bombing Ukrainian cities, including residential areas, universities and schools.… Read more Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more

Interdisciplinary Learning in an Intercultural Setting During Archaeological Fieldwork Since archaeology studies the full spectrum of the human past, it is naturally an academic discipline that engages a very wide range of topics – spanning the humanities, social sciences, physical sciences, and technology. Often, archaeological projects also take place in international settings, with team members joining from around the world. Therefore, archaeological fieldwork offers an ideal laboratory for experimenting with interdisciplinary learning in intercultural settings. Over the last several years, our project has engaged… Read more Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more

Higher education in Cambodia: Reforms for enhancing universities’ research capacities While Cambodian higher education is facing many challenges (see Heng et al., 2022a; Sol, 2021), the major issue that calls for reforms is a limited research capacity of Cambodian universities and academic staff. This problem needs immediate attention. Policy actions are required to improve the research landscape in the country and empower local academics for a more productive and impactful academic performance. In the following sections, I elaborate on my arguments Limited research output:… Read more Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more

Innovation and Liberal Arts Education In the contemporary, globalized, neoliberal landscape of higher education, the increasingly intertwined relationship between government, industry, and universities is changing the nature and mission of higher education. The imperative of economic growth imposes new demands on the type of graduates that are needed to enter the workforce, and consequently on the priorities that universities should set. The call to innovate cannot be ignored if a university wishes to survive. Within the context of higher education,… Read more Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more

Conceptualization and Development of Global Competence in Higher Education: The Case of China The notion of global competence of students increasingly raises concerns among both educational researchers and practitioners. In 2018, the PISA tests assessed global competence of 15-year-old students for the first time (OECD, 2018). According to OECD, such a multidimensional capacity has been identified as the individual ability of examining “local, global and intercultural issues”, understanding and appreciating “different perspectives and world views”, interacting “successfully and respectfully with others, and taking “responsible action toward sustainability and… Read more Quiet Leadership in Schools: A Personal Reflection This article argues for the importance of quiet, introverted leaders in international schools as a counterbalance to the extroverts who seem to make up the bulk of leadership posts in these institutions. It builds on essays by Liz Jackson (2021) and Bruce Macfarlane (2021), which explore leadership in university settings. These authors examine the de facto expectations of leaders to be outgoing and forceful, but challenge the idea of the heroic leader, suggesting that more… Read more

Quiet Leadership in Schools: A Personal Reflection This article argues for the importance of quiet, introverted leaders in international schools as a counterbalance to the extroverts who seem to make up the bulk of leadership posts in these institutions. It builds on essays by Liz Jackson (2021) and Bruce Macfarlane (2021), which explore leadership in university settings. These authors examine the de facto expectations of leaders to be outgoing and forceful, but challenge the idea of the heroic leader, suggesting that more… Read more Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more

Academic Praxis: An Editorial Note The recent special issue which I co-edited with my colleague, Liz Jackson, discussing dilemmas affecting the freedoms of speech, teaching and learning in the post-truth age (see Oleksiyenko and Jackson 2020), points to the importance of developing an academic praxis, in which each of us continually questions the purposes, processes and values of teaching, learning and inquiry. These days, I am increasingly inclined to think of higher learning as a journey of ceaseless introspection, which… Read more