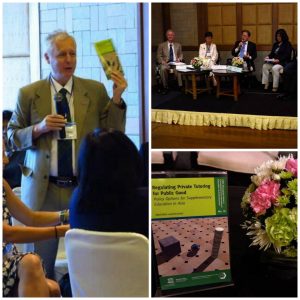

UNESCO’s Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education (UNESCO Bangkok) has today launched a book entitled Regulating Private Tutoring for Public Good: Policy Options for Supplementary Education in Asia.

UNESCO’s Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education (UNESCO Bangkok) has today launched a book entitled Regulating Private Tutoring for Public Good: Policy Options for Supplementary Education in Asia.

The book focuses on the extensive scale of private tutoring in countries of the region, regardless of their development status. For example surveys have found that:

- in Hong Kong, 54% of Grade 9 students and 72% of Grade 12 students receive private supplementary tutoring;

- in India, 73% of children aged 6-14 in rural West Bengal receive tutoring;

- in the Republic of Korea, the proportion reaches 86.8% in elementary school; and

- in Vietnam, respective proportions in lower and upper secondary schooling are 46% and 63%.

The tutoring consumes huge amounts of household finance, and has far-reaching implications for social inequalities, let alone the huge implications it has for school education services. Yet few governments have satisfactory regulations for the phenomenon.

The book’s authors are Mark Bray, UNESCO Chair Professor in Comparative Education at the University of Hong Kong, and Ora Kwo, Associate Professor in the same University. They have worked on this theme for over a decade, much of it in collaboration with UNESCO.

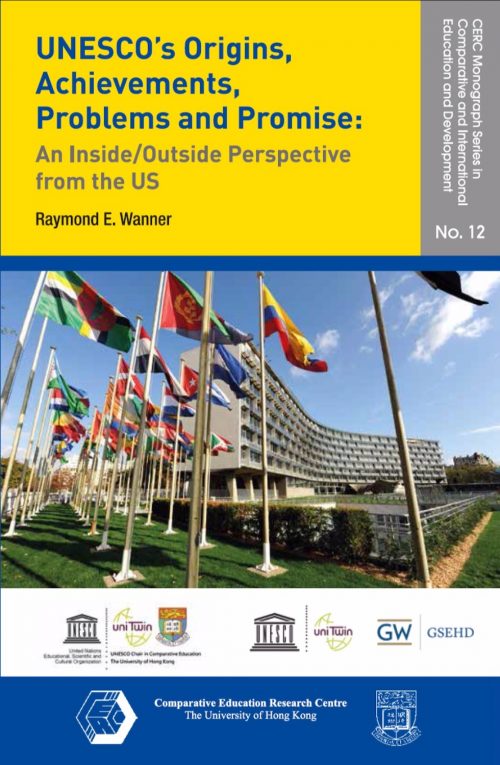

“UNESCO’s mandate permits and demands attention to this important issue,” remarked Professor Bray. “The organization coordinates the global Education for All (EFA) agenda, and leads the shaping of the post-2015 education framework. It is strongly concerned about equitable access to quality education.” UNESCO provides an arena in which governments can learn from each other about policies that are desirable and feasible.

“UNESCO’s mandate permits and demands attention to this important issue,” remarked Professor Bray. “The organization coordinates the global Education for All (EFA) agenda, and leads the shaping of the post-2015 education framework. It is strongly concerned about equitable access to quality education.” UNESCO provides an arena in which governments can learn from each other about policies that are desirable and feasible.

Regulations for teachers and companies

One major question is whether teachers should be permitted to provide private supplementary tutoring. This is permitted in some countries but prohibited in others. Particularly problematic are settings in which teachers tutor the same students for whom they are already responsible during regular school hours. This situation encourages corruption, with the teachers reducing effort during normal hours in order to promote demand for the private lessons.

A separate question concerns companies. Most governments require tutorial companies to register, but are more likely to treat them as businesses than as educational institutions. Regulations for tutoring companies are only beginning to catch up with those for schools, but are arguably almost as important. Governments have a responsibility for overall social and economic development, which includes ensuring an appropriate environment for private sector institutions.

Learning from comparing

Gwang-Jo Kim, Director of UNESCO Bangkok, highlighted patterns in the Republic of Korea (ROK), with which he is intimately familiar as he served as Deputy Minister of Education there before joining UNESCO. The ROK government has devoted most effort to regulations over the longest period. “Yet even ROK has not yet found all the answers,” remarked Mr Kim. “Governments can see the challenges as well as useful strategies in the South Korean case.”

In South and Southeast Asia, in any case, conditions are rather different from those in South Korea. UNESCO has long recognised the diversity in the region, whether in the contexts or in the experiences. The lessons in this book highlight the value of comparisons across countries in all categories.